Philosophy

The idea of the Typological Atlas of Daghestan was to create a tool for the visualization of linguistic features typical of the languages of Daghestan.

Although the language sample underlying TALD has grown to include a number of neighboring languages (more on that in Language sample below), the core of the project remains Daghestan.

Our aim is to achieve maximum coverage of languages and dialects. Datasets on particular topics should be updatable, so that our map visualizations become incrementally more accurate. In order to make the resource updatable, contributors can choose to maintain the right to approve or reject any proposed updates or corrections, or they can choose to waive that right. Note that if you want to stay involved, this also entails a responsibility to review and reply to propositions within a certain time-frame. See Step 5 on how to propose changes to a dataset or chapter that is already published.

Data on linguistic features is collected primarily from descriptive literature; as a result, the Atlas can also be helpful in bibliographical research.

Datapoints

The initial approach of TALD assigned one value for a linguistic feature to each language, based on a representative doculect.

This information could then be mapped onto generalized language datapoints, or all villages where the language in question is spoken.

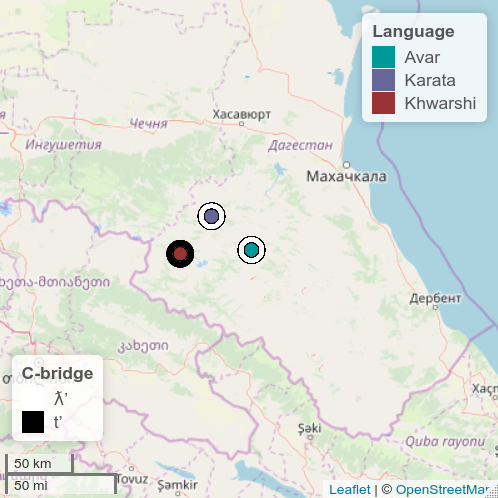

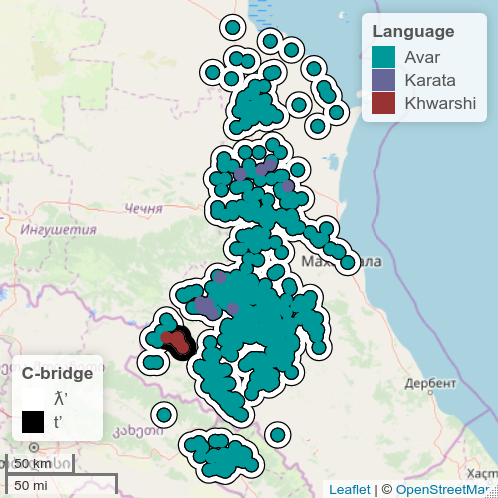

Below are two possible visualizations for the same dummy feature: the initial consonant of various cognates meaning ‘bridge’.

General language datapoints vs. village datapoints

| language | feature | value | form |

|---|---|---|---|

| Avar | Initial consonant of ‘bridge’ | ƛ’ | ƛ’o |

| Khwarshi | Initial consonant of ‘bridge’ | t’ | t’eru |

| Karata | Initial consonant of ‘bridge’ | ƛ’ | ƛ’eru |

A benefit of the visualization on the right, is that it shows the distribution and size of language communities more accurately. A drawback is that it leads to gross overgeneralization and erases dialectal differences, because it is not based on more data than the visualization on the left.

All of the Avar villages, for example, are colored according to data from Standard Avar, while we know that ‘bridge’ in the Zaqatala dialect spoken in Northern Azerbaijan is pronounced kːjo. These villages should thus have a different value.

Current approach

To improve the accuracy of our visualizations, we currently collect all attested values for a given feature, taking into account any idiom we have data on, including standard languages, dialects spoken in multiple villages and single-village idioms.

The visualization shows the most accurate level of granularity available for each village / point on the map.

For example, the Andi language is spoken in 17 villages. There are 9 main villages, each of which has its own idiom. These can be divided into two main dialects: Upper Andi and Lower Andi. In addition, there are 8 villages for which we have no information on the variety spoken there.

Now let us look at a relatively straightforward linguistic feature like Number of noun classes, for which we have general data on both the Upper and Lower dialects, and more accurate information on several villages from the Upper group. One of these villages (Rikvani) even has a value that differs from the other varieties we have data for.

The table below summarizes the different values observed for the language, divided by type of idiom (the number of noun classes is indicated between brackets and each value is color-coded).

| Language | Toplevel dialect | Village |

|---|---|---|

| Andi ● (5) | Upper Andi ● (5) | Rikvani ● (6) |

| Lower Andi ● (3) |

The diagram below shows the dialect grouping of Andi villages and their values for the noun class feature. At the center is the language as a whole: it has the same value as the Upper group and the eponymous village dialect of Andi, which are most representative of the language as a whole. On the map, the unclassified Andi villages (colored grey in the scheme below) will be colored according to the general language information.

The coverage of the Atlas is far from sufficient because we lack data for many dialects, and we do not know the dialect affiliation of a large number of villages in the area. We compensate for this shortcoming by encoding the level of accuracy/granularity for each datapoint, and allowing the user to toggle which levels to display (see Map visualization below). Ideally, our datasets will be updated when new information becomes available.

Map visualization

TALD currently offers three different map visualizations:

- Language and feature shows the language affiliation (inner dot) and the value for the linguistic feature (outer dot) for each village.

- Data granularity allows the user to show only certain levels of data accuracy for the feature. For example you can uncheck “language” to remove all the dots that were colored according to general information about the language in the absence of more accurate data. In this case it will remove all Andi villages that have no dialect classification.

- General datapoints displays one datapoint for each language in the sample, showing the language affiliation (inner dot) and the value for the linguistic feature (outer dot) for each point.

You can click on a datapoint to view a pop-up window with the name of the language (with a link to the Glottolog database), the village, the granularity of data used to color this datapoint, and the value.

1. Language and feature

2. Data granularity

3. General datapoints

The language sample

As mentioned earlier, TALD was originally conceived of as a resource about the languages of Daghestan.

The East Caucasian villages dataset – a dataset that contains a list of villages in the eastern Caucasus, their coordinates, and the languages spoken there – was created as a basis for visualizations in the Atlas. Initially it covered all villages of Daghestan and some East Caucasian speaking communities in Georgia and Northern Azerbaijan.

Villages of Chechnya and Ingushetia, and several more communities in Azerbaijan and Georgia, were added later. It was relevant to include these extra datapoints outside of Daghestan for the development of areal hypotheses.

Northeastern Daghestan

Villages located in the northeastern part of Daghestan are not displayed in the Atlas. This area was settled only relatively recently, and is much more ethnically mixed than the rest of the area, as you can see here. A large part of it remains virtually uncharted (though see Yuri Koryakov’s efforts to close this gap here), and is currently undergoing changes.

In addition, little to nothing is known about the varieties of the languages spoken there. In some cases we know the village of origin for most of its inhabitants (e.g. Novogagatli was founded by settlers from the Andi village Gagatli), but we do not know how well their dialect is preserved and to what extent their population is ethnically and linguistically homogeneous.

Therefore, we decided to exclude the newly settled region from our visualization (for now).

List of languages

Below is a list of the languages included in our sample, grouped by language family and branch.

East Caucasian

- Avar

- Avar

- Andic

- Akhvakh

- Andi

- Bagvalal

- Botlikh

- Chamalal

- Godoberi

- Karata

- Tindi

- Tsezic

- Bezhta

- Hinuq

- Hunzib

- Khwarshi

- Tsez

- Dargwa

- Standard Dargwa

- Chirag

- Itsari

- Kaitag

- Kubachi

- Mehweb

- Tanty

Dargwa is considered a single language with a number of highly divergent dialects by some, and a group of distinct but related languages by others. In our map visualizations with one dot per language, several Dargwa varieties are shown, because they are sufficiently divergent. However, since our data comes from descriptive literature, we are unfortunately bound to some extent to the post 1930s view of Dargwa as a single language. In our villages dataset, for example, a variety like Mehweb forms part of the Northern Dargwa dialect group. We cannot rearrange this underlying tree-structure too drastically for practical reasons.

Unfortunately we do not have a full reference grammar for Chirag yet, so you can leave the row for Chirag empty for now.

- Lak

- Lak

- Lezgic

- Agul

- Archi

- Budukh

- Kryz

- Lezgian

- Rutul

- Tabasaran

- Tsakhur

- Udi

- Khinalug

- Khinalug

- Nakh

- Chechen

- Ingush

- Tsova-Tush (Batsbi)

Indo-European

- Armenic

- Armenian

Armenian appeared in our sample due to a small village in northeastern Daghestan where the language is spoken. Although the village was lost after we removed this area from our visualizations, we decided to keep Armenian as an important language of the region.

- Iranian

- Tat

Kartvelian

- Georgian

Georgian is spoken in the Qakh district of Azerbaijan, alongside Tsakhur and Azerbaijani. It is also an important neighboring language.

Turkic

- Kipchak

- Kumyk

- Nogai

- Oghuz

- Azerbaijani