On phonology of East Caucasian languages

G. Moroz

Last update: November 2021

Plain text

Moroz, George (2021). “On phonology of East Caucasian languages”. In: Typological Atlas of the Languages of Daghestan (TALD). Ed. by Michael Daniel, Konstantin Filatov, George Moroz, Timofey Mukhin, Chiara Naccarato and Samira Verhees. Moscow: Linguistic Convergence Laboratory, HSE University. http://lingconlab.ru/dagatlas.

BibTeX

## @incollection{moroz2020,

## title = {On phonology of East Caucasian languages},

## author = {George Moroz},

## year = {2021},

## editor = {Michael Daniel and Konstantin Filatov and George Moroz and Timofey Mukhin and Chiara Naccarato and Samira Verhees},

## publisher = {Linguistic Convergence Laboratory, HSE University},

## address = {Moscow},

## booktitle = {Typological Atlas of the Languages of Daghestan (TALD)},

## url = {http://lingconlab.ru/dagatlas},

## }1 Introduction

There are many studies dedicated to the phonology of the indigenous languages of the Caucasus, including (Catford 1977; Job, Smeets 1994; Smeets 1994; Alekseev et al. 2001; Hewitt 2004; Grawunder 2017; Beguš 2021; Borise 2021a, 2021b; Koryakov, Maisak Forthcoming), and (Kibrik, Kodzasov 1990) on the East Caucasian languages in particular. There are also many studies on the historical-comparative phonetics of these languages, such as (Bokarev 1960, 1981; Gudava 1964; Imnajšvili 1977; Akiev 1977; Giginejšvili 1977; Talibov 1980; Nikolayev, Starostin 1994; Nichols 1994; Ardoteli 2009; Mudrak 2019, 2020) and many others. Since the amount of grammatical descriptions for particular idioms is increasing, we currently have a lot more information about the phonological inventories represented in specific villages, so we do not need to extrapolate our knowledge of standard languages onto all villages where the language is spoken. Even though we have a lot of material on different East Caucasian languages, in order to be able to compare them we still need a unified description of those inventories. In order to solve this task, I compiled a database of phoneme inventories of East Caucasian and neighboring languages that can be accessed and downloaded here.

On average, East Caucasian languages (as well as other indigenous languages of the Caucasus) have more consonants and vowels than other languages of the world. The main reasons for this are the following:

- the presence of ejective consonants (with the exception of Udi);

- the presence of uvular consonants;

- the presence of lateral obstruents in Andic and Tsezic languages;

- widespread labialization, gemination and fortis/lenis distinction across Dagestan;

- common triangle vowel systems (i, e, a, o, u) are complicated with nasalization (mostly in Andic and some Tsezic languages), long vowels (Nakh, Andic and Tsezic), pharyngealisation and umlaut vowels (in languages spoken in the south, possibly due to Azerbaijani influence).

2 Inventory size

The map below shows the size of the phoneme inventories in languages of the eastern Caucasus:

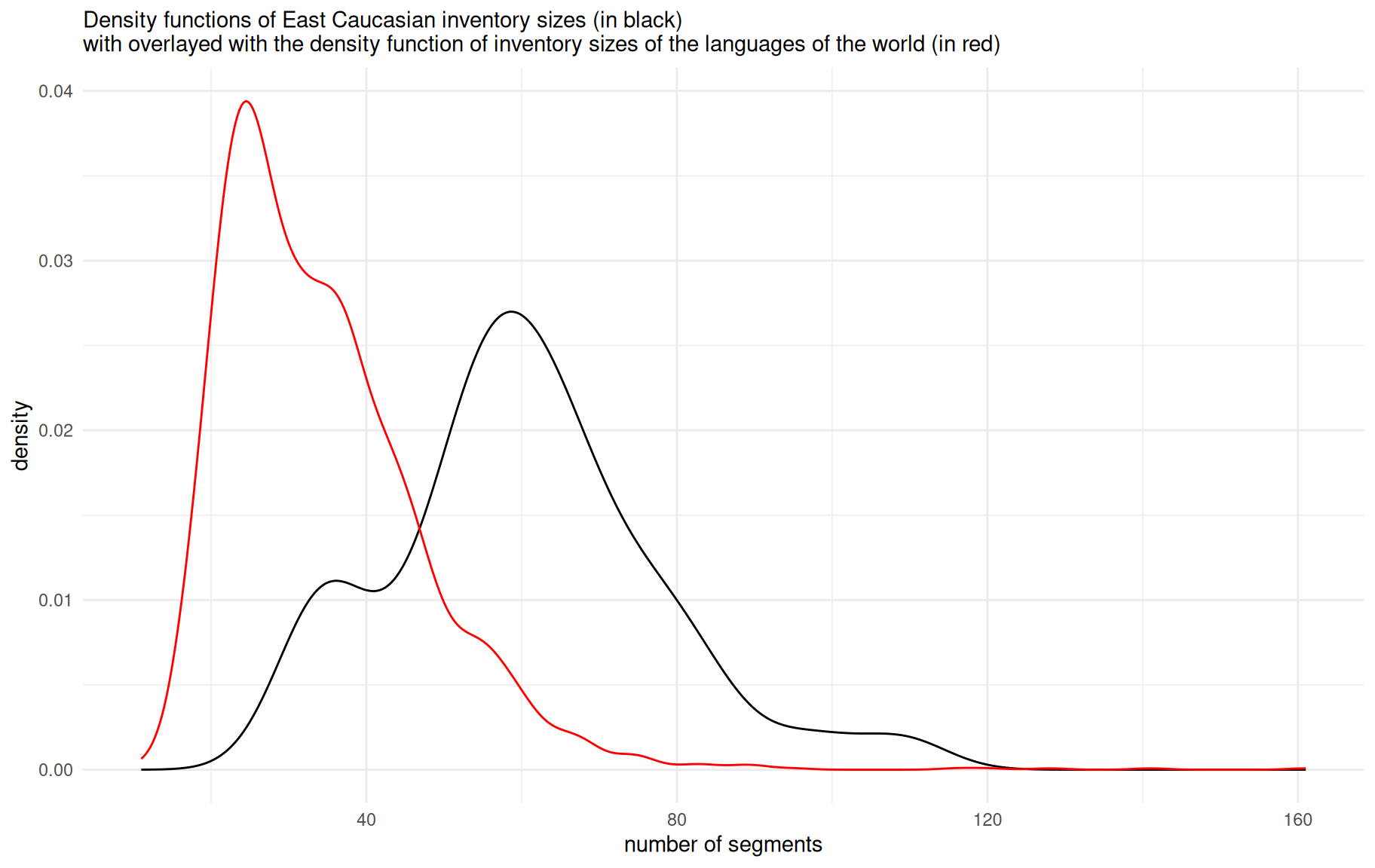

As we can see, the inventory size of the languages in our dataset range from 33 (Georgian and Kumyk) to 109 (Northern Akhvakh). We can compare the obtained numbers with the PHOIBLE database (Moran et al. 2014), which contains phoneme inventories of the languages of the world1:

As demonstrated on the plot, East Caucasian languages in general have big segment inventories (with mean, median and mode near 60 segments) compared to languages of the rest of the world. A small peak around 40 can be explained by the presence of non-indigenous languages in our dataset. Further we will see that overall large inventories are mostly caused by large consonant inventories, although vowels and diphthongs also play a significant role.

2.1 Consonant inventory size

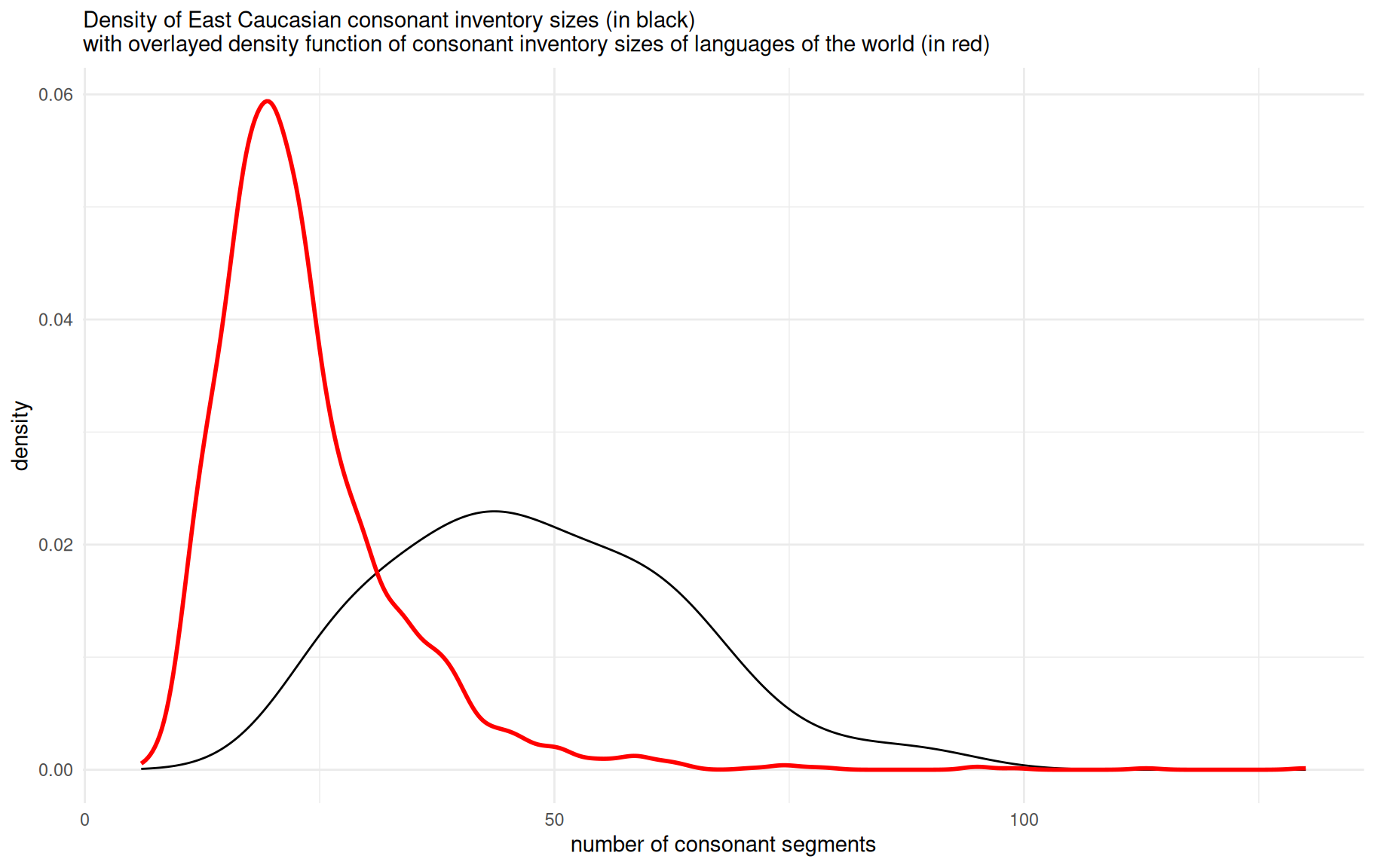

We can compare the consonant inventories in the same way we compared the whole phoneme inventories earlier:

As we can see, the inventory size differs from 25 (Azerbaijani) to 89 (Northern Akhvakh). We can compare the obtained numbers with the PHOIBLE database (Moran et al. 2014):

As demonstrated on the plot, the majority of languages from PHOIBLE have less consonants than East Caucasian languages. This result is caused by different subsystems of East Caucasian languages like ejectives, labialized consonants, uvulars and post uvulars. More or less the same phonological profile can be found in other indigenous language families of the Caucasus — among the West Caucasian languages, for example, we find Ubykh (Fenwick 2011: 16–17), which has one of the largest consonant inventories in the world.

2.2 Vowel inventory size

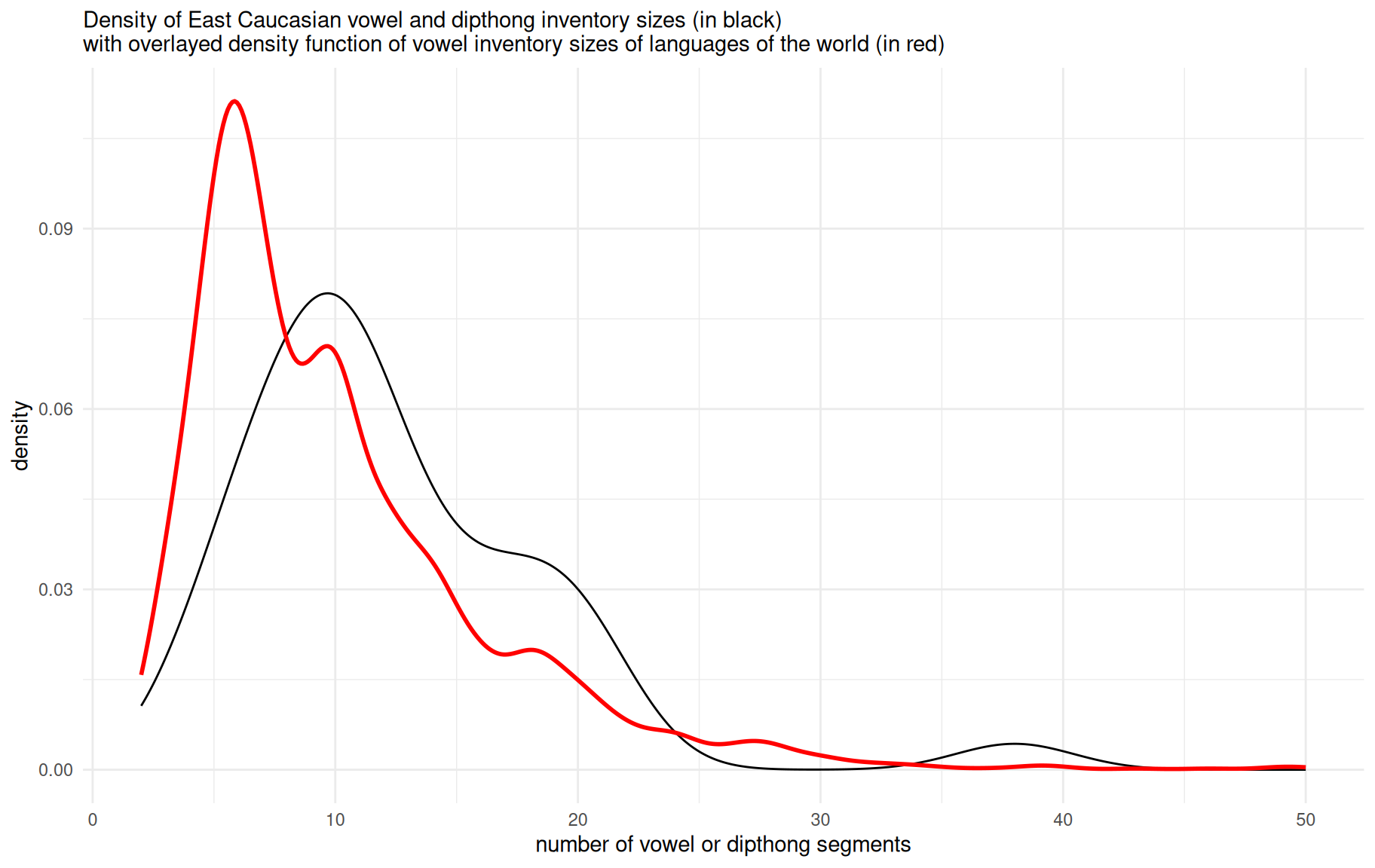

We can do the same comparison for the vowel inventories:

The vowel inventory size ranges from 5 (Avar) to 38 (Chechen). Again we can compare the obtained numbers with the PHOIBLE database (Moran et al. 2014):

As demonstrated in the plot, the vowel/diphthong inventory sizes of East Caucasian languages are slightly bigger than the average of the languages of the world. As expected, the PHOIBLE data reveal an average vowel/diphthong inventory size of around 5, while the East Caucasian dataset shows a mean, median and mode around 10 vowels/diphthongs. Diphthongs are present only in Nakh languages and in Hinuq (Forker 2013). However, it is worth mentioning that the distinction between diphthongs and combinations of vowels and semivowels like j and w is not clear in East Caucasian languages. There is a tendency to have closing diphthongs or combinations of a vowel and a semivowel at the end of the syllable (like ai/aj, eu/ew) and opening diphthongs or combinations of a vowel and a semivowel at the beginning of the syllable (like ia/ja, ue/we). As far as I am aware, there is no phonological difference between diphthongs and combinations of vowels and semivowels in any East Caucasian language. I can stipulate that scholars of Nakh languages tend to describe those units as diphthongs while scholars of Daghestanian languages tend to describe them as combinations of a vowel and a semivowel.

References

When performing such a comparison of our dataset and the one provided by PHOIBLE, the question arises whether we need to exclude East Caucasian and other languages of the Caucasus from the PHOIBLE subsample that we use. In this text we decided to exclude them for the sake of comparability. Not excluding them slightly changed the shape of the density plot shown below, but the change was extremely small. Keep in mind that neither of the samples are balanced, so that they are not ideal for comparison: different language families are overrepresented in both samples, and the sizes of the datasets are different (PHOIBLE’s 2169 languages vs our dataset of 50 idioms) etc.↩︎