About

1 What is TALD?

The Typological Atlas of the Languages of Daghestan (TALD) is a tool for the visualization of information about linguistic structures typical of Daghestan. The project has been developed at the Linguistic Convergence Laboratory. Its scope currently covers all East Caucasian languages and several other languages spoken in Daghestan, Chechnya, Ingushetia and adjacent territories.

The Atlas consists of:

- Chapters describing linguistic phenomena typical of the area (some of the chapters are linked to a major topic, i.e., a more descriptive chapter to which several features are related)

- Datasets with information on particular features

- Map visualizations of how these features are distributed

- A bibliography of literature on languages of the area (see References)

2 Daghestan as a linguistic area

Daghestan is the most linguistically diverse part of the Caucasus, with at least 40 different languages (and many more highly divergent idioms) spoken on a territory of 50,300 km2 that consists mostly of mountainous terrain. The majority of the languages spoken there belong to the East Caucasian (or Nakh-Daghestanian) language family: one of the three language families indigenous to the Caucasus. For the most part, the languages of the East Caucasian family are spoken in the eastern Caucasus area (with the exception of some relatively recent diasporic communities). They have no proven genealogical relationship to any other languages or language families.

Other languages spoken in Daghestan include three Turkic languages: Nogai, Kumyk (Kipchak) and Azerbaijani (Oghuz); and three Indo-European languages: Russian (Slavic, the major language of administration, education, and urban areas), Armenian (Armenic), and Tat (Iranian). Arabic is the language of religion, as most people in Daghestan are Sunni Muslims. The official languages of Daghestan (in alphabetical order) are Agul, Avar, Azerbaijani, Chechen, Dargwa, Kumyk, Lezgian, Lak, Nogai, Russian, Rutul, Tabasaran, Tat, Tsakhur.

Historically there was no single lingua franca for the whole area. As a result, Daghestanians were known for having a command of multiple locally important languages, which they picked up in the course of seasonal labor migration, trading at cardinal markets, and other types of contact. Currently these patterns are disappearing fast due to the expansion of Russian.

One of the aims of TALD is to chart the genealogical and geographical distribution of linguistic features and to facilitate multi-faceted analyses of language contact in Daghestan by comparing the presence of shared features with known patterns of bilingualism and lexical convergence.

The list of languages included in our sample is available in the section Languages.

3 Map visualizations

The Atlas currently offers four different types of map visualizations:

- General datapoints

- Extrapolated data

- Data granularity

- Tile map

Each of these visualizations has its benefits and drawbacks, so we allow the user to toggle between different options.

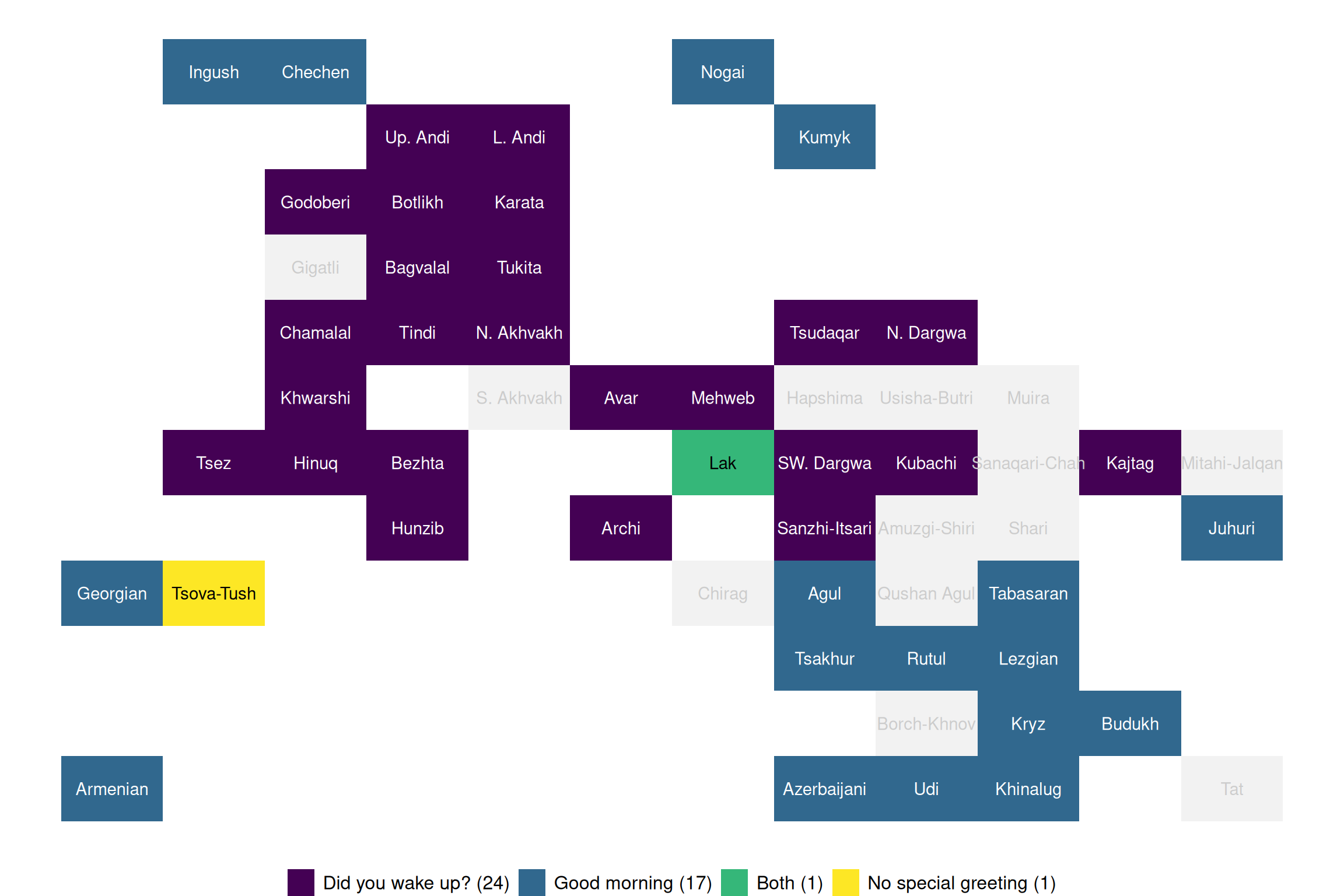

Below are some examples from the chapter on Morning greetings, which describes the two main ways to greet someone in the morning in the languages of Daghestan: wishing them a good morning or asking them whether they woke up.

For map visualizations we use the Lingtypology package (Moroz 2017) and the RCaucTile package (Moroz 2025) for R.

3.1 General datapoints

This is the more basic visualization, which shows one dot on the map for each language in the sample. The inside of each dot is colored by language. Languages from the same group have similar colors (e.g., all Lezgic languages have some shade of green). Hover over a dot to see the name of the language, and click to view a popup with a link to the language’s page in the Glottolog database. The color of the outer dots indicates the value of a linguistic feature. By unticking the checkbox “show languages” you can remove the inner dots and visualize the distribution of different values in the area without the distraction of genealogical information.

3.2 Extrapolated data

This visualization represents each language as a cluster of dots, which correspond to villages where a certain language is spoken. This visualization makes use of the East Caucasian villages dataset that contains information on village names, geographical coordinates, and genealogical classification (including dialects).

A benefit of this type of visualization is that it shows the size and boundaries of speech communities (as opposed to maps based on abstract general datapoints). Its main drawback is that it involves a lot of generalization. We do not have information on each village variety of the languages in our sample, so we extrapolate the information we have on a certain variety to all the villages where they are spoken. In doing so, we risk overgeneralizing information and erasing possible dialectal differences.

Note, however, that extrapolation is performed in a bottom-up fashion, so if we have data for a certain village variety that differs from other varieties of the same dialect group for a specific feature, we do not extrapolate data to that village.

3.3 Data granularity

In the data granularity visualization one dot on the map corresponds to one datapoint collected by the author. Each dot is colored according to the genealogical classification. The possibles values are: language, top level dialect, non-top level 1 dialect, non-top level 2 dialect, non-top level 3 dialect, and village dialect. For example, “village dialect” indicates that we had information about the feature for a specific village variety, while “language” means that we only had information for the language in general.

This allows the user to see what kind of data underlies the default visualization.

Our aim for the Atlas is to continue adding new data to existing datasets and thus gradually improve its coverage and accuracy.

3.4 Tile map

This visualization is analogous to the General datapoints visualization but displays languages as rectangles and allows for color-coding based on specific linguistic values. The Tile map visualization was designed specifically for TALD with the R package RCaucTile (Moroz 2025).

4 Contribute to the Atlas

The chapters and datasets in the Atlas are created by researchers specializing in the languages of Daghestan as well as by students of linguistics with no prior knowledge of the area and the languages spoken there.

If you would like to contribute a chapter and / or data to the Atlas because you are studying a certain topic in the languages of Daghestan, or you are a student looking for an internship, do not hesitate to contact us! You can find our contact info under Team.

To get a better idea of our methodology and what you will have to do if you decide to become a contributor, see our Contributor Manual.

5 Access to the data

The data can be accessed through the Atlas interface, or downloaded directly from our GitHub page. For reasons of space, on the Atlas interface we show filtered versions of the original databases, which only include the main information displayed on maps. However, both filtered and full versions of the databases are available for downloading. Full versions including more detailed information for each observation in the database (e.g., specific morphemes or wordforms, examples of their occurrence in texts with glosses and translations) can be downloaded by clicking on the download button, or by accessing our GitHub page.

6 How to cite

6.1 Plain text

Moroz, George, Michael Daniel, Konstantin Filatov, Timur Maisak, Timofey Mukhin, Irina Politova, Elena Shvedova, Samira Verhees, and Chiara Naccarato (2026). Typological Atlas of the Languages of Daghestan (TALD), v. 2.0.1. Moscow: Linguistic Convergence Laboratory, HSE University. DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.6807070. https://lingconlab.ru/tald.

6.2 BibTeX

@book{tald2026,

title = {Typological Atlas of the Languages of Daghestan (TALD), v. 2.0.1},

author = {George Moroz and Michael Daniel and Konstantin Filatov and Timur Maisak and Timofey Mukhin and Irina Politova and Elena Shvedova and Samira Verhees and Chiara Naccarato},

year = {2026},

publisher = {Linguistic Convergence Laboratory, HSE University},

address = {Moscow},

url = {https://lingconlab.ru/tald},

doi = {10.5281/zenodo.6807070},

}